Time Series Prediction

Analysis and Predition of Time Series for Polimi Competition

I worked on this project for a competition during the course of Artificial Neural Network and Deep Learning in Politecnico di Milano. I worked with Dr. Francesco Azzoni and Dr. Corrado Fasana.

Analysis of the Data

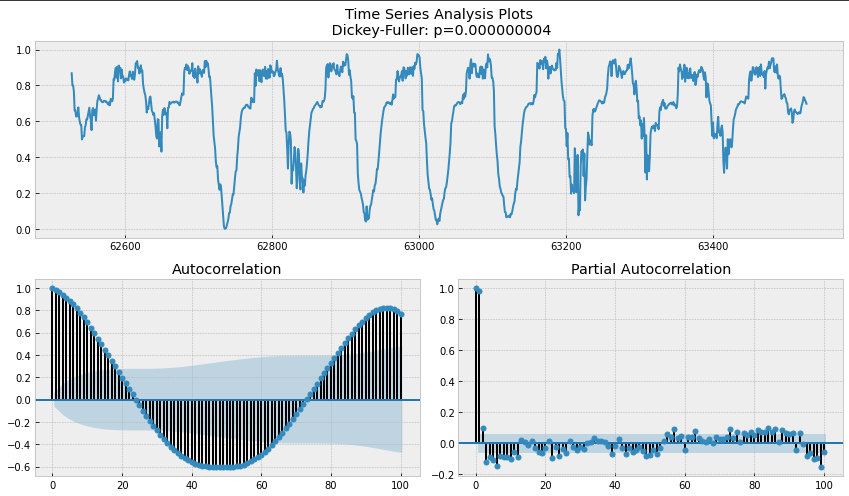

The data is a multivariate time series with 7 features, with different ranges and without evident outliers. Before proceeding with modelling we normalized the data with MIN-MAX normalization and analyzed it using time-series decomposition. In doing this, we noticed high correlation between some pairs of features (Crunchiness - Hype root; Loudness - Wonder level). By looking at the autocorrelation and partial-autocorrelation plots, it seems that the variables can be modelled using an AR model given that the PACF has a hard cut-off at a certain lag. Moreover, the ACF plot shows a high correlation between the value of the time series at time $t$ with that at time \(t-96\). This highlights the presence of a seasonality that can be easily visualized plotting the time series.

By plotting the series it is possible to notice that there are intervals of time in which features show a constant value (maybe data-glitches). For this reason, we created a copy of the training set, removing these portions paying attention to keep seasonal properties unchanged. To do this, we removed slices of 96 elements at the time.

Data preparation

To perform a proper splitting, we had to define 3 hyper-parameters: window, stride and telescope. We split the dataset in training and validation sets that have \(window\) common samples. This is done to perform the evaluation also on the first \(telescope\) samples after the training set, that otherwise would only be considered as part of the \(window\) and never used to evaluate the metrics.

\[\label{eq:split} (set\_size - window - telescope) \; \% \; stride == 0\]The size of the sets is trimmed in order to ensure that the equation holds. This is done to avoid using padding when building the sequences that constitute a batch. Thus part of the oldest samples are removed during this procedure. We normalized both training and validation sets with MIN-MAX normalization and we built sequences starting from them.

Scheduled Sampling

Since we use a value for the \(telescope\) that is smaller than the number of samples that we need to forecast, we need to use an auto-regressive procedure. To improve the quality of the predictions during the regressive steps we applied a scheduled sampling procedure: the idea is to initially let the model learn on the original sequences for a certain number of epochs, then start substituting (with an increasing probability) some portions of the sequences with values predicted by the model. In this way the model learns how to perform predictions based on its own past predictions. This should avoid the risk of having performance drop during forecasting after the first autoregressive step. However, in the end, we noticed that models without scheduled sampling outperformed the same models with scheduled sampling.

Hyper-parameters tuning

At the beginning, the different models were tried with standard hyper-parameters, to get a baseline over the possible performances. Then, in order to tune them in a better way, a grid-search hold-out cross-validation was performed. Anyway, working in the local environment, we faced some problems due to the limited amount of resources, partially tackled using packages like Ray. For this reason, we did not perform cross-validation for the more complex models used later on.

Regularization

In order to avoid overfitting, we combined different regularization techniques. In particular, we used early stopping during the training procedure and we built most of the models with the inclusion of some dropout layers.

Models

In order to address the task, we built several models with different types of architectures and different parameters. As already said, the parameters used in the first models were those found using cross-validation. However, for complex models, we performed some trials and errors to find satisfiable parameters.

Hierarchical LSTM

Initially, we started by building simple models composed of up to 2 or 3 stacked LSTM cells with and without convolutional layers. This was not expected to give outstanding performances given the simplicity of the model but the results could then be used as a baseline for further models. In particular, we also tried to use the same models with GRU cells and using bidirectional LSTMs. In the end, the resulting predictions appeared quite smooth w.r.t. the real time-series appearance and the performance on the hidden test was not lower than 4.2 for what concern the RMSE.

Vanilla Transformer

After the different trials using methods that make use of recurrent connections, we decided to try to use a transformer to improve the performances using self-attention mechanism and positional encoding instead of RNNs. Transformers should be more efficient and accurate on long-range predictions, since they are able to process a longer input sequence and detect the most relevant features to produce the next output. The architecture that we initially used is the one shown in the paper “Attention Is All You Need”, composed by several encoder and decoder blocks and self-attention mechanism. The input of the decoder during training is composed by the last value (or the last few values) of the encoder input and then the true target values until we compose a sequence of length \(telescope\). A look-ahead mask must then be applied in the decoder attention layers to make sure that values at step \(t+i\) are not used to compute the attention scores of values at step \(t\). The performance was good during training, but pretty bad in prediction. This is probably caused by the Teacher Forcing learning method used as training procedure: the model relies too much on the decoder input and thus learns to produce as output this same input, because it is very similar to the true target (it is just shifted). During the prediction phase instead, it is not the true target that is fed to the decoder but the value predicted at the previous time-step(s), thus the learned strategy performs poorly. For this reason we tried to decrease the number of true values fed to the decoder, but the performance did not improve much.

Customized Transformer

Given the previous results, we decided to try to remove the decoder part completely and only keep the encoder blocks. For this reason, the general architecture that we used was composed of a set of self-attention layers (with multi-head attention) followed by a few dense layers in order to perform the final prediction. Given that no recurrent components are used, it is necessary to provide some further information that allows the model to take into account time and ordering of the values of the time series. This was addressed using time embedding (or positional encoding in the case of the Vanilla transformer). In particular, we used Time2Vec.

According to the paper in which this embedding was presented, Time2Vec gives a vectorial representation of time with periodicity, invariance to time rescaling and simplicity. For a given scalar notion of time \(\tau\), Time2Vec of \(\tau\) , denoted as \(t2v(\tau)[i]\), is a vector of size \(k + 1\) defined as follows:

\[t2v(\tau)[i]= \begin{cases} \omega_{i}\tau + \phi_{i},& \text{if} \; i = 0. \\ \mathcal{F}(\omega_{i}\tau + \phi_{i}),& \text{if} \; 1 \leq i \leq k. \\ \end{cases}\]where \(t2v(\tau)[i]\) is the \(i^{th}\) element of \(t2v(\tau)[i]\), \(\mathcal{F}\) is a periodic activation function, and \(\omega_{i}\)s and \(\phi_{i}\)s are learnable parameters.

Thus, in the end, the time series is passed through the embedding layer before being fed to the transformer. One of the most important aspects to be considered is related to the dimension of the embedding representation provided by Time2Vec. Initially, we set it to 1 and tried to check whether the transformer was able to achieve promising performances. Of course, also the number of attention layers, the number of heads and other parameters like the dropout rate should be properly tuned. After trying the previous model, we realised that the results were already comparable to those provided by the hierarchical LSTM architectures. Thus, we proceeded by experimenting with different hyper-parameters values and with the use of scheduled sampling. In this way, we were able to reach better performances, the best providing a RMSE of around 3.50 on the hidden test set. During these experiments, we found that suitable Time2Vec dimensions were 2 or 5 and that the use of different window, stride an telescope could have a big impact on the performances too. Moreover, we also noticed that using ELU and SELU activation functions provided better results than a classic RELU. In the end, we also tried to use RMSProp optimizer instead of Adam but the latter showed almost always better results. Finally, another important aspect is the learning rate scheduler. In fact, the use of different learning rate schedulers impacted the stability of the learning process and the capability of converging faster.

Customized Transformer 2.0

In the previous models we always used dense layers after the flat vector of features extracted by the Transformer. In this architecture instead we took the output of the attention blocks, that has a shape of (None, window, features), and sliced it along the dimension $1$ to have several blocks of shape (None, period, features) capturing the information of just one seasonality. Those blocks are first processed separately to extract the most useful features and to reduce the depth, feeding them to a small network composed by: a 1D convolutional layer, a flattening layer, a dense layer and a reshape layer resulting in a shape of (None, period, target_features). Then they are concatenated along a new axis producing a 4D tensor of shape (None, period, target_features, blocks). A series of 2D convolutional layers is used to extract the relevant patterns, reducing after each one the temporal dimension using a stride greater than 1. After them a 1x1 2D convolutional layer is used to change the depth of the tensor in order to match the desired output size (telescope x target_features), and then a GAP layer is added to combine together the dimensions 1 and 2 resulting in a tensor with shape (None, 1, 1, telescope x target_features). The last operation is to reshape the features to achieve the desired output shape (None, telescope, target_features). We tuned the hyper-parameters of this architecture and after some trials and errors we managed to achieve a better performance w.r.t. the previous models. In particular, we were able to reach a RMSE on the hidden test of 3.41 using the original dataset. Instead, when we moved to the use of the cleaned dataset, keeping the same model, the RMSE on the hidden test decreased to the value 3.33.

Model ensemble

As last try, we performed model ensemble using the best models constructed so far. Thus, the final prediction was computed as the average of the prediction provided by each model. The final performance was slightly better than before (3.32). In the end, we also tried to perform model ensemble using a fully convolutional meta-learner trained on top of the predictions provided by the other models.

Other useful information

We tried to train the models considering either the MSE or the MAE as loss function. In the end, the MAE seems to be a better choice. Finally, before submitting the models we always performed a full training of them using the whole dataset.